Learn proper pronunciation. Study the complete American English sound system; vowels, consonants, words, and sentence construction. Then read dialogues and speeches reviewing vocabulary for Kitchens, Bedrooms, Bathrooms, Business English, Internet terms, Clichés, Anatomy, Nursery, and Citizenship.

Search This Blog

Thursday, July 30, 2020

Saturday, July 25, 2020

Friday, July 24, 2020

Order of speech development.

Between six

and nine months, babies babble in syllables and start imitating speech

sounds. By twelve months, a baby’s first

words usually appear and by eighteen months to two years children use around

fifty words and will start putting short sentences together.

Exercise 1:

Review the list of words aloud.

Exercise 2:

Create a sentence for each word.

Practice

sound and word

|

1.

|

- p: pa

- m: ma

- h: ha

- n: no

- w: woo

- b: bee

- k: key

- g: game

- d: did

- t: toy

- ng: ring

- f: farm

- y: you

- kw: quick

- bl: black

- br: brick

- dr: drink

- fl: flu

- fr: free

- gl: glee

- gr: great

- kl: clean

- kr: crumb

- pl: plan

- st: street

- tr: trail

- sl: slope

- sp: speed

- sw: sweet

Thursday, July 23, 2020

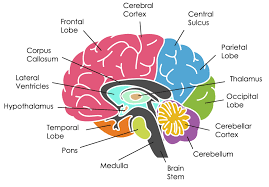

Clean your brain

A type of brainwave may help clean your brain while you sleep

MIND 31 October 2019

By Layal Liverpool

Fultz et al. 2019

As you sleep, slow waves of electrical activity in your brain seem to help rinse away harmful waste products that could otherwise damage your brain cells. The process may play a role in preventing neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.

“Sleep is really important for clearing toxic metabolic waste products from the brain,” says Laura Lewis at Boston University, Massachusetts. Sleep deprivation is associated with a build-up in the brain of clumps of protein, such as beta-amyloid, which is implicated in Alzheimer’s disease, she says.

Brainwaves are made by large networks of brain cells firing together in rhythm. Much about their function is unclear, but we know they are slower during deep sleep, and faster when we are awake. To see if brainwaves play a role in cleaning the brain, Lewis and her team used EEG caps to measure electrical activity in the brains of 13 people while they napped inside MRI scanners.

At the same time, the researchers also measured blood oxygen levels in their brains and the flow of cerebrospinal fluid, a watery liquid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord.

Flowing in and out

They found that, during sleep, large waves of cerebrospinal fluid flow into and out of the brain every 20 seconds, a process thought to remove waste. The inward flow was preceded by patterns of slow waves of electrical activity, called delta waves.

These brainwaves are also known to play a role in consolidating memories while we sleep. The researchers found that the waves coincided with blood flowing out of the brain, which they say helps balance the total volume of fluid around the brain.

People with neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s have fewer and weaker slow brainwaves, says Lewis. “So we might expect that there are also fewer and smaller waves of cerebrospinal fluid in those disorders, and that might have an impact on how waste products are cleared.”

Read more: The brain’s drain: How our brains flush out their waste and toxins

However, it isn’t clear yet whether impaired brain cleaning during sleep might be a cause or a symptom of conditions like Alzheimer’s.

Just one bad night’s sleep can lead to more beta-amyloid building up in the brain. But there is no need to panic. “Sometimes when people haven’t had enough sleep, they’ll actually show much more of these electrical slow waves the next night,” says Lewis . “That might be a way for the brain to make up for some of that lost sleep.”

Read more: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2222016-a-type-of-brainwave-may-help-clean-your-brain-while-you-sleep/#ixzz6T1xtYmp6

MIND 31 October 2019

By Layal Liverpool

Fultz et al. 2019

As you sleep, slow waves of electrical activity in your brain seem to help rinse away harmful waste products that could otherwise damage your brain cells. The process may play a role in preventing neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.

“Sleep is really important for clearing toxic metabolic waste products from the brain,” says Laura Lewis at Boston University, Massachusetts. Sleep deprivation is associated with a build-up in the brain of clumps of protein, such as beta-amyloid, which is implicated in Alzheimer’s disease, she says.

Brainwaves are made by large networks of brain cells firing together in rhythm. Much about their function is unclear, but we know they are slower during deep sleep, and faster when we are awake. To see if brainwaves play a role in cleaning the brain, Lewis and her team used EEG caps to measure electrical activity in the brains of 13 people while they napped inside MRI scanners.

At the same time, the researchers also measured blood oxygen levels in their brains and the flow of cerebrospinal fluid, a watery liquid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord.

Flowing in and out

They found that, during sleep, large waves of cerebrospinal fluid flow into and out of the brain every 20 seconds, a process thought to remove waste. The inward flow was preceded by patterns of slow waves of electrical activity, called delta waves.

These brainwaves are also known to play a role in consolidating memories while we sleep. The researchers found that the waves coincided with blood flowing out of the brain, which they say helps balance the total volume of fluid around the brain.

People with neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s have fewer and weaker slow brainwaves, says Lewis. “So we might expect that there are also fewer and smaller waves of cerebrospinal fluid in those disorders, and that might have an impact on how waste products are cleared.”

Read more: The brain’s drain: How our brains flush out their waste and toxins

However, it isn’t clear yet whether impaired brain cleaning during sleep might be a cause or a symptom of conditions like Alzheimer’s.

|

| Oxygenated blood (red) in a sleeping brain |

Read more: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2222016-a-type-of-brainwave-may-help-clean-your-brain-while-you-sleep/#ixzz6T1xtYmp6

MRI study reveals all mammals, including humans, share equal brain connectivity

July 21, 2020 Animals, Brain, Health & Medical

MRI study reveals all mammals, including humans, share equal brain connectivity

TEL AVIV, Israel — Mankind’s collective ego may be about to take a big hit. Humans have always reigned supreme on planet Earth when it comes to intelligence. Indeed, it’s our intellect and capacity for critical thinking that primarily separates us from the rest of this planet’s inhabitants. That’s why the findings of a new study are so surprising. Researchers from Tel Aviv University, after examining and comparing brain connectivity across 130 different mammalian species (including humans), conclude that brain connectivity is equal among all mammals.

These findings, reached via MRI brain scans, oppose long-standing beliefs and assumptions among medical and scientific professionals.

“We discovered that brain connectivity — namely the efficiency of information transfer through the neural network — does not depend on either the size or structure of any specific brain,” says Professor Yaniv Assaf, of the School of Neurobiology, Biochemistry and Biophysics, in a release. “In other words, the brains of all mammals, from tiny mice through humans to large bulls and dolphins, exhibit equal connectivity, and information travels with the same efficiency within them. We also found that the brain preserves this balance via a special compensation mechanism: when connectivity between the hemispheres is high, connectivity within each hemisphere is relatively low, and vice versa.”

Brain connectivity compared via MRI scans

Many scientists theorize, or assume, that the human brain features far more intricate levels of connectivity in comparison to other mammals. But, this study author’s weren’t so sure.

“We know that key features are conserved throughout the evolutionary process. Thus, for example, all mammals have four limbs. In this project we wished to explore the possibility that brain connectivity may be a key feature of this kind — maintained in all mammals regardless of their size or brain structure. To this end we used advanced research tools,” explains study co-author Yossi Yovel, a professor at the School of Zoology.

So, advanced diffusion MRI brain scans were taken of 130 animals, with each mammal representing a different species. A wide variety of mammals are included in the research, from bats to dolphins. Meanwhile, 32 humans had their brains scanned as well. MRI scans detect and illuminate white matter in the brain, allowing the research team to reconstruct each mammal’s neural network.

One’s neural network consists of the neurons and axons that move information around, and the synapses where those neurons meet.

Next, the study’s authors had to figure out how to accurately compare scans of different mammals with one another. For example, comparing an MRI scan of a bear to a squirrel represented a challenge due to the drastically different sizes/structures of the two animals’ heads. To overcome this difficulty, researchers utilized Network Theory (a branch of mathematics). This approach facilitated the creation of a way to universally measure brain conductivity in mammals of all shapes and sizes. In simpler terms, the research team counted the number of synopses a piece of information must pass through go from one place to another in a neural network.

“A mammal’s brain consists of two hemispheres connected to each other by a set of neural fibers (axons) that transfer information,” Professor Assaf says. “For every brain we scanned, we measured four connectivity gages: connectivity in each hemisphere (intrahemispheric connections), connectivity between the two hemispheres (interhemispheric), and overall connectivity. We discovered that overall brain connectivity remains the same for all mammals, large or small, including humans. In other words, information travels from one location to another through the same number of synapses.

“It must be said, however, that different brains use different strategies to preserve this equal measure of overall connectivity: some exhibit strong interhemispheric connectivity and weaker connectivity within the hemispheres, while others display the opposite,” he notes.

Adds Yovel: “We found that variations in connectivity compensation characterize not only different species but also different individuals within the same species. In other words, the brains of some rats, bats, or humans exhibit higher interhemispheric connectivity at the expense of connectivity within the hemispheres, and the other way around — compared to others of the same species.”

The professor suggests that future studies could investigate how different types of brain connectivity impact “various cognitive functions or human capabilities such as sports, music, or math.” In the meantime, Assaf believes the work reveals the existence of a new universal law among mammals: Conservation of Brain Connectivity.

“This law denotes that the efficiency of information transfer in the brain’s neural network is equal in all mammals, including humans. We also discovered a compensation mechanism which balances the connectivity in every mammalian brain. This mechanism ensures that high connectivity in a specific area of the brain, possibly manifested through some special talent (e.g. sports or music) is always countered by relatively low connectivity in another part of the brain. In future projects we will investigate how the brain compensates for the enhanced connectivity associated with specific capabilities and learning processes,” he explains.

The study is published in Nature Neuroscience

MRI study reveals all mammals, including humans, share equal brain connectivity

TEL AVIV, Israel — Mankind’s collective ego may be about to take a big hit. Humans have always reigned supreme on planet Earth when it comes to intelligence. Indeed, it’s our intellect and capacity for critical thinking that primarily separates us from the rest of this planet’s inhabitants. That’s why the findings of a new study are so surprising. Researchers from Tel Aviv University, after examining and comparing brain connectivity across 130 different mammalian species (including humans), conclude that brain connectivity is equal among all mammals.

| Oxygenated blood (red) in a sleeping brain |

“We discovered that brain connectivity — namely the efficiency of information transfer through the neural network — does not depend on either the size or structure of any specific brain,” says Professor Yaniv Assaf, of the School of Neurobiology, Biochemistry and Biophysics, in a release. “In other words, the brains of all mammals, from tiny mice through humans to large bulls and dolphins, exhibit equal connectivity, and information travels with the same efficiency within them. We also found that the brain preserves this balance via a special compensation mechanism: when connectivity between the hemispheres is high, connectivity within each hemisphere is relatively low, and vice versa.”

Brain connectivity compared via MRI scans

Many scientists theorize, or assume, that the human brain features far more intricate levels of connectivity in comparison to other mammals. But, this study author’s weren’t so sure.

“We know that key features are conserved throughout the evolutionary process. Thus, for example, all mammals have four limbs. In this project we wished to explore the possibility that brain connectivity may be a key feature of this kind — maintained in all mammals regardless of their size or brain structure. To this end we used advanced research tools,” explains study co-author Yossi Yovel, a professor at the School of Zoology.

So, advanced diffusion MRI brain scans were taken of 130 animals, with each mammal representing a different species. A wide variety of mammals are included in the research, from bats to dolphins. Meanwhile, 32 humans had their brains scanned as well. MRI scans detect and illuminate white matter in the brain, allowing the research team to reconstruct each mammal’s neural network.

One’s neural network consists of the neurons and axons that move information around, and the synapses where those neurons meet.

Next, the study’s authors had to figure out how to accurately compare scans of different mammals with one another. For example, comparing an MRI scan of a bear to a squirrel represented a challenge due to the drastically different sizes/structures of the two animals’ heads. To overcome this difficulty, researchers utilized Network Theory (a branch of mathematics). This approach facilitated the creation of a way to universally measure brain conductivity in mammals of all shapes and sizes. In simpler terms, the research team counted the number of synopses a piece of information must pass through go from one place to another in a neural network.

“A mammal’s brain consists of two hemispheres connected to each other by a set of neural fibers (axons) that transfer information,” Professor Assaf says. “For every brain we scanned, we measured four connectivity gages: connectivity in each hemisphere (intrahemispheric connections), connectivity between the two hemispheres (interhemispheric), and overall connectivity. We discovered that overall brain connectivity remains the same for all mammals, large or small, including humans. In other words, information travels from one location to another through the same number of synapses.

“It must be said, however, that different brains use different strategies to preserve this equal measure of overall connectivity: some exhibit strong interhemispheric connectivity and weaker connectivity within the hemispheres, while others display the opposite,” he notes.

Adds Yovel: “We found that variations in connectivity compensation characterize not only different species but also different individuals within the same species. In other words, the brains of some rats, bats, or humans exhibit higher interhemispheric connectivity at the expense of connectivity within the hemispheres, and the other way around — compared to others of the same species.”

The professor suggests that future studies could investigate how different types of brain connectivity impact “various cognitive functions or human capabilities such as sports, music, or math.” In the meantime, Assaf believes the work reveals the existence of a new universal law among mammals: Conservation of Brain Connectivity.

“This law denotes that the efficiency of information transfer in the brain’s neural network is equal in all mammals, including humans. We also discovered a compensation mechanism which balances the connectivity in every mammalian brain. This mechanism ensures that high connectivity in a specific area of the brain, possibly manifested through some special talent (e.g. sports or music) is always countered by relatively low connectivity in another part of the brain. In future projects we will investigate how the brain compensates for the enhanced connectivity associated with specific capabilities and learning processes,” he explains.

The study is published in Nature Neuroscience

Wednesday, July 22, 2020

Thoroughly or Throughout

Thoroughly (thur-oh-lee): I thoroughly enjoyed this week’s English class.

Throughout (throo-out): They talked throughout the movie, so I have no idea what was said.

Throughout (throo-out): They talked throughout the movie, so I have no idea what was said.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)